Executive summary

Apprehensions of fresh refugee outflows from Afghanistan grew tremendously after the mid-August 2021 Taliban takeover of the country. At the time, hopes for a positive outcome seemed to depend entirely on how the Taliban ruled and how western countries engaged with the regime.

Four months later, few of those early hopes have come to fruition. Western sanctions against the Taliban are still as firmly in place; Afghanistan’s assets abroad remain frozen and international economic support for the regime continues to be suspended. At the end of 2021, there were few signs of imminent formal international recognition or direct international engagement on the one hand, and none at all of an inclusive government in Kabul, which has been a clear precondition for any form of international recognition for the Taliban rule. Concerns over human rights, particularly women’s rights, in Afghanistan only grew in the last four months of 2021. Poverty, difficulties for the economy and the humanitarian challenge progressively worsened during that time.

All these factors have contributed to increasing the challenges facing the Afghans and added to their desperation. Against this backdrop, the specter of mass exodus of Afghans has only magnified with each passing month.

Voluntary repatriation of Afghans from Pakistan has all but ended since the Taliban return to power and the UNHCR has noted an increasing number of Afghans crossing into Pakistan. That may not be surprising, considering that all of the push factors seem to be in full force with few pull factors in sight.

Cross-border outflows from Afghanistan have historically slowed down or halted in the generally harsh winter season, resuming with the onset of the spring. Unless there is clear realization of those early hopes from August last, growing footfall out of the Afghan territory seems all but inevitable.

The key stakeholders, particularly the usual destination countries for Afghans, do not appear to have made the best use of time to prepare financially, logistically or in terms of public perceptions for that eventuality.

Post-August 2021 Afghanistan

In a little over four short months of the Taliban takeover of Kabul, challenges for Afghanistan on the political, diplomatic, economic and humanitarian fronts have either remained unchanged or deteriorated considerably.

Pakistan and Iran have been two of the main host countries for the Afghan population since the 1979 Soviet invasion. There are in Pakistan over 1.4 million registered Afghans, who carry proof of registration (PoR) cards and their voluntary return is facilitated by the UN refugee agency, the UNHCR. Pakistan has a further 1.5 million unregistered Afghans as well.

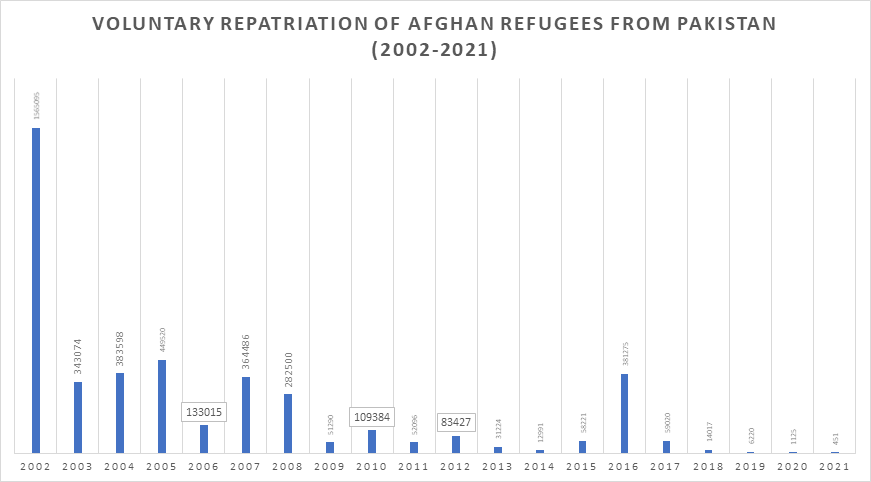

In recent years, the number of Afghans in Pakistan availing the UNHCR voluntary repatriation program has gradually fallen, largely due to growing alarm over the security situation in Afghanistan.

Source: UNHCR

Over the previous decade, the highest voluntary repatriation of Afghans from Pakistan in any single year was recorded in 2016 (381,275 individuals). That was also the only time in the past decade when the voluntary returns topped 100,000 in a year. The lowest repatriation number, by far, was in 2021. In fact, the voluntary return of only 451 Afghans from Pakistan in 2021 was the lowest for any year, at least since the turn of the century.

If slowing repatriation was one measure of the sentiment among displaced Afghans, a clear, if not yet exponential, rise in new arrivals in Pakistan from that country was another. In the last five months of 2021, the UNHCR documented as many as 72,125 new arrivals from Afghanistan to Pakistan.[1]

Stumbling blocks: then and now

There has been little movement in the continuing stalemate of demands from both the Taliban regime and the international community, particularly western countries, since mid-August last.

The Taliban crave engagement and at least some form of recognition. By the beginning of 2022, not even a single country had either formally recognized the Taliban regime or taken any discernable step towards that move. Kabul’s chief benefactor Islamabad had also not shown the slightest inclination towards recognizing the regime. A Taliban appeal for at least Muslim nations to recognize them has also not found any takers so far.[2]

Although the US and the UN Security Council gave in December some exemptions for basic supplies of food and medicine, western sanctions aimed at the Taliban remain in place. International funding to Afghanistan is suspended and billions of dollars of the country’s assets abroad, mostly in the US, continue to be frozen since August last.

Formal recognition by Western nations has seemed contingent largely on formation of an inclusive dispensation in Kabul and respect for human rights, particularly women’s rights.

There have not been many promising developments on the inclusive government front in Kabul since the Taliban takeover. In fact, it is still uncertain what sort of governance model the regime will prefer, and whether any form of democracy would be practiced. In December, the Taliban dissolved the Independent Election Commission of Afghanistan, which was tasked with administration of elections, arguing that there was “no need” for such a commission.[3] The move is the latest setback to democracy’s prospects in Afghanistan.

Despite many promises from the Taliban regime about women’s rights, a number of recent decisions have appeared geared towards imposing restrictions on women in public life.

In December, a guidance issued by the Taliban Ministry for the Promotion of Virtue and Prevention of Vice called on all vehicle owners to offer transport to women seeking to travel only if they were accompanied by a close male relative.[4] The guidance stated that the hijab would also be required for women seeking transport.

A month earlier, the ministry had decreed that “female journalists in [electronic] media should observe Islamic hijab” and asked Afghanistan’s television channels to stop showing dramas and soap operas featuring women actors.[5] Afghan girl students, particularly in colleges and universities, still await clarity on resumption of their education.

Furthermore, despite an amnesty decree by the Taliban when they returned to power in August, a number of reports hint at reprisal attacks.[6]

A Human Rights Watch report[7] in late November stated that Taliban fighters had summarily killed or forcibly disappeared more than 100 former police and intelligence officers since taking power in Afghanistan.

In December 2021, the United Nations expressed alarm over ‘credible allegations’ of over 100 extrajudicial killings in Afghanistan since August. It said that at least 72 of those killings were attributed to the Taliban.

Add to that general context the growing difficulty of everyday existence in Afghanistan and the intensity of desperation for the average Afghan becomes apparent. There is the economy that is crippled to the point that it is a monumental challenge to pay salaries to public servants, even to healthcare staff. The Afghan currency lost a quarter of its worth in the first four months of Taliban rule. The banking sector has nearly collapsed. But perhaps most alarming of all, the kind of impetus needed to counter the momentum on any of these fronts is conspicuous by its absence.

What the future holds

Amid the post-Taliban state of governance, economy, security and human rights, a fresh wave of Afghans fleeing in search of safety and survival seems inevitable — unless the Afghans see definite hope for a safe future in their own country.

No such hope had materialized as 2021 came to a close. There seemed little chance of an inclusive government. The winding up of Afghanistan’s Election Commission did not inspire confidence of any democratic progress in the country in the near future. Curbs on women’s freedoms have started becoming more pronounced. Despite assurance of amnesty, accounts of reprisal attacks and extrajudicial killings are coming to light.

In the final analysis, no amount of food and humanitarian support would take the Afghans away from the fact that a safe and somewhat prosperous future is eluding them.

In short, not only have developments in Afghanistan post-August failed to alleviate key concerns about their future among a large number of Afghans, they have also added fresh reasons for many to contemplate flight.

Furthermore, reported friction over Pakistan’s border fence along Durand Line, and possibly over dealing with the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan militants based in Afghanistan, can further complicate the Taliban regime’s ties to their closest, if not the only, patrons in the region. That could have serious implications for the already critical humanitarian situation in Afghanistan as well as a direct impact on the displacement situation.

Over the last several decades, displacement regularly ebbs in harsh winters and resumes with the arrival of spring. The UN refugee agency has not reported considerable cross-border movement of Afghans into Pakistan since the change of regime in Kabul. That can change very quickly as the snow starts melting. The small window for preventing the latest exodus from Afghanistan has only grown smaller as the Afghans look to an uncertain 2022. There is little indication so far that the key stakeholders, particularly the usual destination countries for Afghans, have made the best use of the time or shown the urgency to prepare financially, logistically or in terms of public perceptions for that eventuality.

[1] Https://data2.unhcr.org/en/documents/download/90388

[2] Taliban PM calls for Muslim nations to recognise Afghan government, France 24, January 18, 2022, https://www.france24.com/en/live-news/20220119-taliban-pm-calls-for-muslim-nations-to-recognise-afghan-government

[3] ‘No need’: Taliban dissolves Afghanistan election commission, Aljazeera, 25 December 2021, ttps://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/12/25/taliban-dissolves-afghanistan-election-commission

[4] No trips for Afghan women unless escorted by male relative: Taliban, Dawn, December 26, 2021, https://www.dawn.com/news/1665938

[5] Taliban instruct female television anchors to wear hijab Dawn, November 22, 2021, https://www.dawn.com/news/1659589

[6] Afghan women protest against ‘Taliban-killings’ of ex-soldiers, Dawn, 28 December 2021, https://www.dawn.com/news/1666306/afghan-women-protest-against-taliban-killings-of-ex-soldiers

[7] “No Forgiveness for People Like You”, Human Rights Watch 30 November 2021, https://www.hrw.org/report/2021/11/30/no-forgiveness-people-you/executions-and-enforced-disappearances-afghanistan#9322